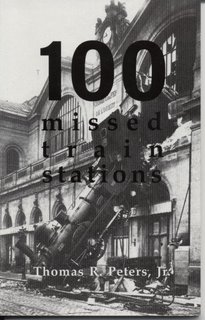

100 Missed Train Stations by Thomas R. Peters, Jr.

Farfalla Press, Boulder, CO 2002

A Review by Andy Hoffmann

Catapulted like dice I rise

Head-on like a matador on sleeping pills

I'm bruised by long distance love

& you're on the roof looking at the stars

from "L"

Tom Peters likes movement, likes to be going somewhere. And as he indicates in the title

of his recent collection of poems, 100 Missed Train Stations, you've got to be on the

train to miss the stations, you've got to be rolling to have a chance to stop. And as the

poems themselves suggest, you've got to be crazy in love with your trip and the metaphors

you ride. You've got to bleed from the tongue, so to speak, smoke from the asshole, you've

got to come ready to bone and get boned in a "sea of flashbulbs." In the end, there are no

easy answers, no easy situations, but as long as you're still talking, as long as you've

got something to say, there's always that fragmented chance (the roll of the dice) that

you might talk yourself into a future where longing meets love, where dry puckered lips

actually join those of the beloved, a kiss of language, an intoxicating mouth-to-mouth

exchange. Yes, but this kind of poetic juice doesn't come without a warning, for, as

Peters writes, "All's fair in love & the darkness/with silence dancing in my heart/a good

view means nothing to a drowning man." Love, darkness, silence, heart, dying. Add to that

nachos, a bottle of tequila and cable TV and you've got the picture.

It's the most tender story, this "catapulted" man trying to keep his head above water,

this trip, these stops, these sonnets, a hundred enigmatic poems, this tenuous and often

humorous search for love. But these poems aren't tender, not in the least, aren't meant to

be. In fact, they're a response to tenderness, to poetry that takes itself too seriously.

Working from collage and creating an edge by stunning simile (techniques that won't allow a

line to run itself into easy understanding), Peters shares the world of a man who has sat

for many hours behind the wheel of an eight cylinder gas guzzling Buick looking ahead at the

black road, the impossible horizon, passing through the corn, finally stopping for gas and a

plate of eggs and sausage where he might scratch a poem on a napkin to Caitlin, the well-

mothered antagonist of so many of these lyrics. It is at this precise moment, while sitting

in a diner, he discovers mineral water will never quench his thirst, and because of this he

must turn his attention to the waitress and the "tempo" in which she "returns his pesos."

These poems, these sonnets, however, are not narrative in the sense that I've just

described. Indeed what's most important to these poems is the tempo; the only time they keep

is to the beat that carries the word. And craft. 100 sonnets, 100 train stops. Titles that

expertly seep into the poems. Why not. Why not have the title, "98 bottles of beer on the

wall," for a piece wherein the poet reflects on "Yesterday's problems... falling in one

continuous circle," and in doing so, recognizing a terrifying spiral that makes him "tremble

in fear of meaning." Of course. The search for meaning is over and done with, and when the

edge of that cliff is reached, certainly it's frightening-frankly, we're all scared shitless

of the darkness at the edge of nothing. Paradoxically, each of the hundred sonnets are

elegantly formed, as if in the end it's the shape of the thing that really matters. While I'm

not suggesting that Peters is especially influenced by Aristotle, in a sense 100 Missed Train

Stations is about form as much as it is about anything. So Peters the formalist (one of his

many hats) tends to do what formalists do, that is, write poetry about poetry, even if he's

grinning from ear to ear as he does it. And because of the form the book becomes necessarily

retro and almost nostalgic. That is, as we roll across the land in subject matter, always

going forward toward future, seeking a lover that is never quite there, we also look to the

past in a need to ground our meandering in an accepted form. Peters dwells in the past,

emphasizes it, comes home to it like Kerouac to his mother. Or should I say father, because

the past that Peters returns to is, to be precise, manmade.

It would be hard to talk about 100 Missed Train Stations without giving due credit to

Ted Berrigan, whose Sonnets have been particularly inspirational for those most influenced

by the New York School, as Peters no doubt is. Of Berrigan, David Shapiro writes, "Ted's

poetry wove between poles of fullness of content and a taste for the humiliations of

experiment." He goes on to say that his work is the "literary equivalent of 'Pop' art" and

"as chaste and fine and humble as anything in the Arte Povera movement that followed Pop

Art." The same could be aid for Peters the poet, Peters the pop culture whiz kid, Peters

the one who remember, the man who loves steel and aluminum, the man who loves women, the

man who turns the abstract sensuous, Peters the provacateur, the midnight boy, the

emotional, the keen-hearted, the fresh, a present day Apollinaire. Ted Berrigan's Sonnets is

a great experiment, an important book. Tom Peters' 100 Missed Train Stations not only stands

upon Berrigan's experiment, but extends it. Peters' work is ambitious, challenging, edgy,

expertly crafted and full of surreal grace. Peters makes me laugh, yes-and these days,

laughter is not a small thing. I also leave this book feeling like I need a road trip. I

need to breakdown and "sit poised/next to the car on the side/of the road," and while

watching the sunset, think of those I need to love, perhaps recall an angry kiss, and most

certainly hope against hope for Montana.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home